How Asian Is It?

Curated by Lilly Wei

Emily Cheng, David Diao, Shirley Kaneda, Il Lee, Kikuo Saito, Shen Chen, Barbara Takenaga

Walasse Ting, Richard Tsao, Kim Uchiyama, Robert Yasuda, and Charles Yuen

Opening on February 13, 2026 – July 11, 2026

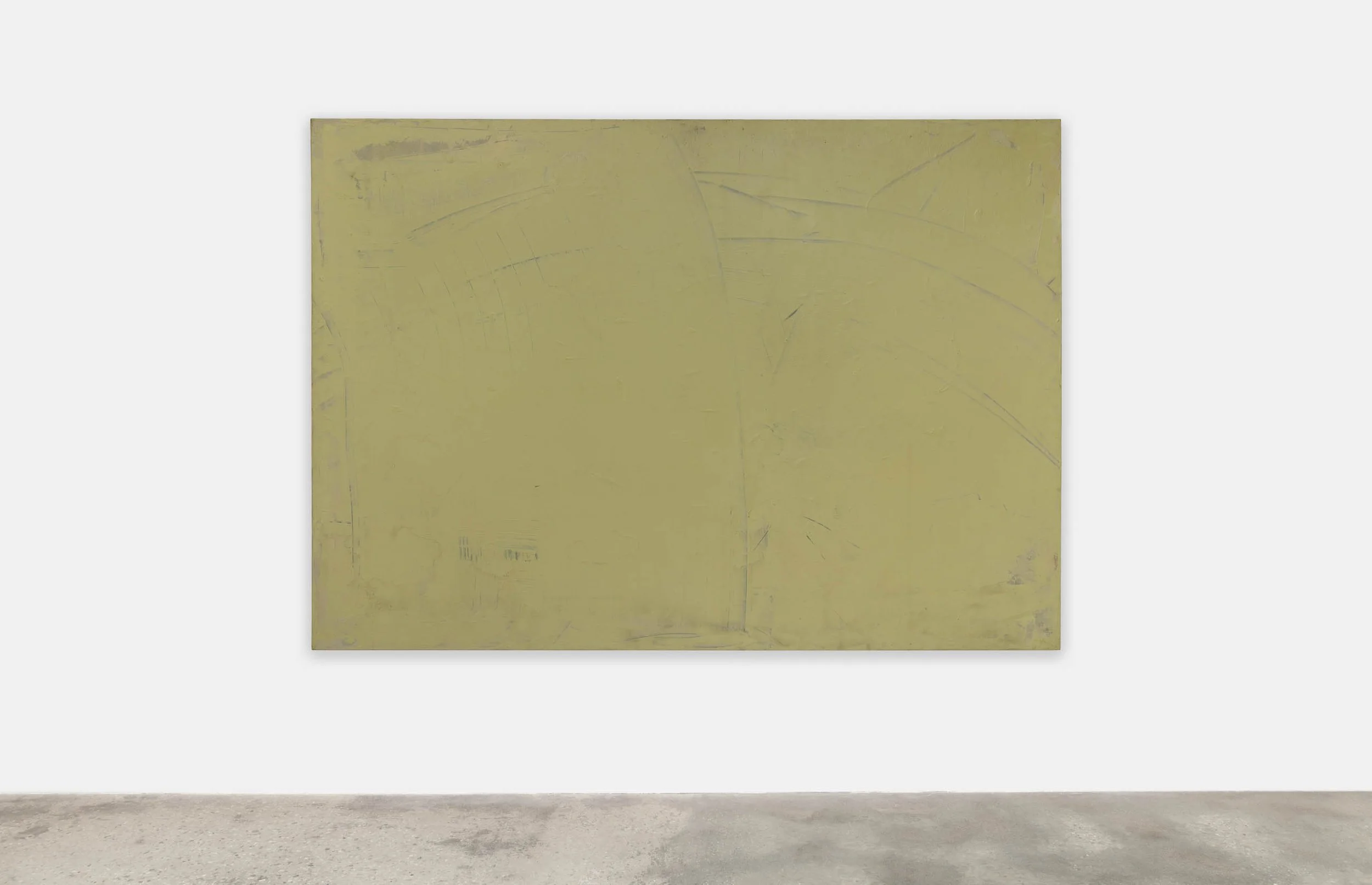

David Diao

Grandsweep, 1970

acrylic on canvas, 79 × 112 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York

Photo: Júlia Standovár

The category Asian American was meant to stamp people of Asian descent as a group with a sense of shared identity. Yet at the same time, it qualified that identity. We never say European Americans, or White Americans; they are simply Americans. There were also other problems with the term, chief among them the lack of any great commonality or cohesiveness as might be expected across a land as vast as Asia with its diverse populations and cultures. Rather than allies, many were historical enemies, and had been for centuries, even millennia. America, however, was meant to be a place of new beginnings, of reconciliations, new affiliations, and rewritten narratives.

The participants in this exhibition, How Asian Is It?, are all (East) Asian American abstract painters of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean descent which was an intentional as a logistical choice. All born in the last century, they were shaped by experiences that differ greatly from today’s Asian American artists who view such designations as part of community building, networking, even branding, as an ideological, political, and marketing identification. They understand that it is empowering to belong to a community, even an imagined one, Asian American as a larger grouping than Chinese American, Japanese American, Korean American. Formerly, however, artists—and not just Asian American artists—were warier of categorization by race, ethnicity, gender, and similar labels that might be perceived as pejorative or restrictive, afraid that it might further marginalize them. They would not have willingly called themselves Asian Americans, although that has now changed.

By the 1950s, Abstract Expressionism was dominant, making New York the new global nexus of the art world. The work of Asian American abstract painters, however, was viewed as derivative, peripheral, or simply ignored. (Asian American figurative artists whose subjects were socio-politically themed fared somewhat better.) By the 1960s, as minimalism and conceptual trends took hold, Asian Americans attained some institutional attention but remained underrepresented in mainstream discourse. By the 1970s, these artists were increasingly active in alternative spaces and artist-run initiatives, even as major New York art institutions continued to ignore their contributions. By the 1980s, multiculturalism and identity politics dominated the discussion, accompanied by a proliferation of not-for profit art spaces in New York, creating greater visibility for Asian American artists, including abstractionists, although this visibility was often based on ethnicity and extra-aesthetic criteria.

It was a trend that continued into the 1990s to the present. Artist-run organizations, community institutions, and university galleries played a critical role in the dialogue and helped build audiences for work that was still not shown often enough in leading museums and other art venues. But even as New York and the art world became more international, welcoming successive waves of contemporary Japanese, Chinese, and Korean artists with open arms and much critical (and commercial) acclaim (most were figurative painters, conceptualists, installation, performance artists or artists of timed-based media), Asian American abstract painters continued to be sidelined. Long considered not American enough, they were now dismissed as not Asian enough (and often not current enough), a kind of falling into the space between the two words.

Today, influenced by revisionist art history and the growing interest in diasporic artists and transnationalism, a new generation of critics and curators, including those who are themselves Asian American have been instrumental in integrating these artists into the broader discourse of postwar and contemporary abstraction—as has the increasing numbers of Asian and Asian American collectors, gallerists, and benefactors, and, significantly, the resurgence of abstract painting itself.

The 12 artists in How Asian Is It?, were born between 1928 and 1955, many of whom have been under-recognized until recently. The origins of all these artists are from different regions of the world, their exposure to that heritage varying from great doses to none. As their locations, their lives, and the discourse changed, as they converged on New York, so did their thinking about that legacy and the impact it had on their work. As America shifted from assimilation to the notion of an interlocking mosaic to today’s (siloed) enclaves and subcultures, separatism (and divisiveness) now defines us, countered by the connective forces of globalization and transnationalism.

Artists are not predictable nor is the art they make—which is as it should be. Artists should also be free to make the work they choose to make, and not be compelled to pursue choices that have been determined for them, the hallmark of all democratic societies. So, how Asian is it? How American?

The better question might be: how can these works of art contribute to a better world? How civilizing are they? How humane? How truthful? Art that can do that is more needed than ever.

*Essay excerpt from Lilly Wei. More information about the exhibition coming soon.